Stefano Milioni ‘s excursus on pasta continues. We go through literature to discover the differences between dry and fresh pasta.

As we have seen in past episodes, pasta is a poor, humble product, invented to preserve the food staple from easy spoilage, and to ensure a food reserve in the event that the next distribution of grain might skip, due to a famine, a gale that had prevented ships from reaching the port of Rome, or a more serious infestation than the others in the grain stores.

Pasta, therefore, was in fact born in Imperial Rome and could only be born in a place where, simultaneously, the following three conditions occurred:

- A city of more than a million inhabitants that depended on external supplies, with no integration with agriculture in the surrounding area;

- The periodic succession of famines that kept alive in people’s the specter of starvation;

- The difficulty of storing grain beyond a certain perioddue to their perishability, a phenomenon that while serious at the level of collective supply, became dramatic at the level of individual families for whom, as monthly grain distributions were lacking, they did not know where to go to get more food.

It is because of this miserable origin of pasta that we owe the fact that very little is said about it in the literature of the time.

A gap in the literature

It is not mentioned because until the nineteenth century, when people wrote about gastronomy they did so predominantly by talking about the powerful and the rich, who, certainly, even in Imperial Rome did not eat pasta.

Or by exalting (as it still does today) the dream of rural life in which rustic and simple products are the stars of the everyday table.

But pasta has no relation to the life of farmers., it is a product for survival in a big city, and this is not an endearing subject for a poet.

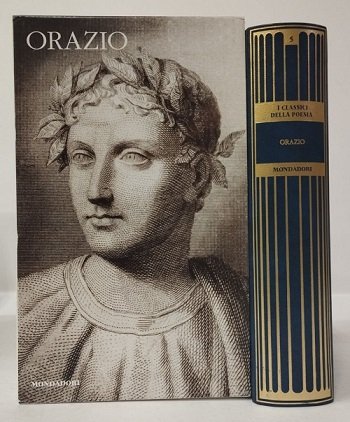

Unless you are a countercultural poet like Horace, who liked to flaunt attitudes at odds with the life led by the powerful among whom he lived.

In the sixth Satire of the first Book, demonstrating a healthy and peaceful life he writes “…so (in the evening) I return home to a bowl of chickpea leeks and lagane.”. Well, those “lagane,” a name still used in many southern regions, are none other than our lasagna.

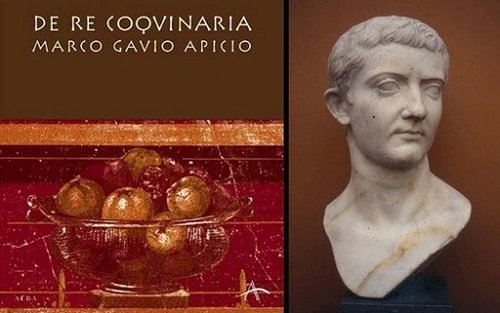

After Horace, it will also be discussed by Apicius in his De re Coquinaria, mentioning them as an ingredient in many dishes, never bothering to explain how they should be made, and this shows how common they must have been among the Romans at that time, since an accurate explanation is always given for every other element.

Horace’s lasagna vs. Apicius’ lasagna

If we analyze the two texts well, however, we will find that there is a difference between Horace’s lasagna and Apicius’ lasagna.

The former are a poor food, thrown into the pot to prepare frugal, simple food. The latter are the ingredient in a refined dish, elaborate, requiring long preparation and the skilled hand of a cook.

The former are dry pasta lasagna, the latter fresh pasta lasagna.

Fresh pasta

And in later centuries, if we have evidence of “pasta” in literature and historical records, it will always be fresh pasta, prepared in the kitchens of kings and the powerful, enriched in the dough with eggs, reduced to strips, squares, rolled and stuffed with precious mixtures of meat, fish and vegetables: agnolotti, tortellini, ravioli.

And that fresh pasta was the food of the rich and powerful even before the conditions for the invention of dry pasta occurred in Rome is evidenced by the oldest evidence of pasta in Italy, in the tomb of the Cerveteri reliefs (the tomb of a powerful man, then) in which are reproduced in stucco, on the two central pillars, the tools for working pasta by hand: the pastry board, the rolling pin, the bag for dusting the flour on the board, the ladle for the water, the knife for cutting the pastry sheet, and the wheel for giving a wavy bodo to the pasta.

Dry pasta

As for the dry pasta, there is little or no evidence for about a millennium, and it is always lasagna or similar formats. Only after the year 1000 do we have the first evidence of other pasta formats, particularly the ” vermicelli” (tria) that were definitely of Arab origin and were produced in Sicily and exported to the rest of Italy.

And the famous “macaroni“, at least in the early days are not a well-defined format: that word was used to identify different shapes of pasta, such as gnocchi or balls crushed with fingers or with special tools, all made with the same technique, that of crushing.

The invention of new formats becomes more vivid after 1300, but we are still in a restricted sphere, confined to local customs and not the sign of an evolution towards industrial production: pasta is still a reserve food product, a guarantee for the future, consumed periodically not as a primary food habit, but because of the need to renew stocks.

Freely excerpted from “RuvidaMente.com,” courtesy of the author.