This Wednesday, Stefano Milioni takes us to Naples to find out that the “mangia mangiiamaccheroni” became such only through Spanish rule. And that dry pasta awaited a foreign guest to become a gourmet dish.

Contrary to what anyone would imagine, until the 18th century, pasta was not a primary food in Naples. In fact, until that time, Neapolitans were called ” leaf-eaters” due to the prevalence of vegetable consumption in their diet.

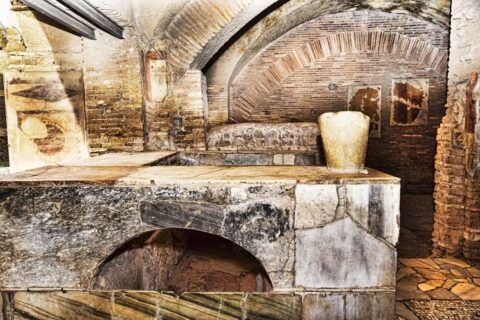

But, with the advent of Spanish rule, characterized by unwise management of public administration, the problems of food supply shortages became more frequent and more severe, and this became the impetus for a massive use of dried pasta as a food supply, dry pasta that becomes increasingly reliable in this respect thanks to the use in its production of two new “machines”, the kneading machine and the press, which make it possible to obtain, for the first time, a pasta similar in structure and end result to that which we eat today.

From “leaf-eater” to “big-eater”

The continuation of this state of emergency throughout the Spanish rule meant that the Neapolitans, over the course of two centuries were transformed from “leaf-eaters” into “candy-eaters” and by this name were known everywhere from the 18th century onward.

Once again, we see that pasta becomes the emblem of a people not because of gastronomic merits, because it was a food that gave pleasure and that one was proud to eat, but solely to fight hunger and poverty.

In the same years, in fact, and up to the threshold of the 19th century, in the homes of the nobles and the powerful triumphed fine cuisine, rich in fresh and filled pastas and their use slowly spread among the wealthier classes, evidenced by the increasingly frequent opening, especially in the cities of northern Italy, of pasta stores, specialized artisans who always prepared and sold only fresh pasta.

An all-Italian invention

After this quick walk through the centuries, we can safely say that dry pasta is a uniquely and typically Italian culinary invention and whose preparation and consumption spread throughout Italy due to a combination of numerous events and socio-historical conditions.

At the same time, pasta seems to have been biding its time for centuries, waiting for a catalyst that would provide the impetus necessary for it to reach its full potential: elevation to the status of a primary foodstuff capable not only of satisfying hunger but also of delighting the palate.

A food for the poor

Until the 18th century, the consumption of pasta was essentially reserved for the poor, who adopted it mainly because of its long shelf life and exceptional nutritional value, not because they found it particularly appetizing. It was usually Boiled and eaten alone or flavored, at most, with a little grated cheese.

As a dish, it presented little or no refinement and no fuss was made in presenting it. The vermicelli were taken from the plate with the hands and brought to the mouth, without much ceremony.

Only when it was combined with tomatoes pasta became a real “dish” and a dietary staple, inspiring cooks to devise recipes to be published and disseminated.

We will discuss this extensively next week.

Freely excerpted from “RuvidaMente.com,” courtesy of the author.